We examined direct and interaction effects of learners' characteristics (cognitive ability, prior knowledge, prior experience, and motivation to learn) and classroom characteristics (videoconferencing and class size) on learning from a...

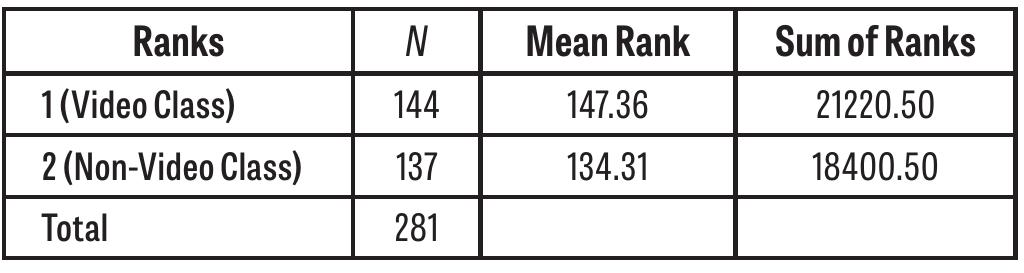

moreWe examined direct and interaction effects of learners' characteristics (cognitive ability, prior knowledge, prior experience, and motivation to learn) and classroom characteristics (videoconferencing and class size) on learning from a 16-week course. A 2x2 quasiexperimental design varied the class size between large (~ 60 students) and small (~ 30 students) and between traditional classes with the instructor always present and classes taught using a videoconferencing system with the instructor present at each site every other week. Theory regarding instructor immediacy was used to predict that larger and videoconferenced classes would have negative effects on learner reactions and learning, but that highly motivated learners would overcome the negative effects on learning. Interactions between videoconferencing and motivation to learn, and class size and motivation to learn, were found in support of the theory. Research and practice implications are discussed. Videoconferencing and Class Size 1 The Effects of Video Conferencing, Class Size, and Learner Characteristics on Training Outcomes Videoconferencing is becoming more widespread as a training medium (Sugrue, 2003). Advantages of videoconferencing relative to traditional classroom instruction include greater convenience for people at remote sites and reduced travel expenses. Relative to other forms of distance training, videoconferencing has the advantage of having higher levels of synchronous, verbal interaction between the instructor and learners. Because of the possibility for this type of 2-way interaction, videoconferencing is considered the distance training method closest to classroom instruction (Moore & Kearsley, 1996), and is being used by many corporations and universities (Webster & Hackley, 1997). Research to date has provided few prescriptions about when videoconferencing is appropriate. Most models of training effectiveness suggest that both situational and individual factors have effects on training outcomes (Mathieu, Tannenbaum, & Salas, 1992). Yet, few situational and individual factors have been examined in research that compares videoconferencing to other means of delivering training. As a result, it is unclear under what circumstances, and for which learners, videoconferencing would be an appropriate delivery technology. Reviews of delivery technology research revealed that many studies in this area are case studies, and thus it is difficult to draw conclusions about causal relationships (Russell, 2001). Moreover, quasi-experimental research in this area has been criticized for not adequately controlling for differences in instructional method (Clark, 1994) and learner characteristics (such as learner motivation and mental ability) that could explain differences in outcomes across conditions. Studies typically confound multiple variables and are thus unable to clearly attribute observed differences between training conditions to any one particular factor. Videoconferencing and Class Size 2 One quasi-experimental study that avoided confounds of different instructors, content, and methods was Sugrue, Rietz, and Hansen (1999). The authors examined learner performance in the same graduate level finance course, delivered by the same instructor, using the same materials, across traditional classroom and videoconferencing delivery methods. The authors also controlled for relevant individual difference characteristics, including general mental ability (GMA). They found that learners with poor pre-training attitudes did better on exams in classes where the instructor was always physically present compared to videoconferencing from a remote location. Theoretically, the physical presence of the instructor created a more motivating situation than videoconferencing, so learners were more likely to pay attention, less likely to be distracted, and thus more likely to learn. In communications research, instructor behaviors that motivate learners have been referred to as immediacy behaviors (Andersen, 1979). Unfortunately, the Sugrue et al. (1999) study does suffer from a confounding variable. Sugrue et al. (1999) compared small and large videoconferenced course delivery to small faceto-face delivery, but they did not have data from a large, face-to-face class. Because average class size was not equivalent across the videoconferenced and non-videoconferenced versions of the course, the research design was unbalanced and videoconferencing effects may have been confounded with class size effects. Theoretically, class size can influence outcomes in ways similar to videoconferencing; larger classes may decrease student motivation and thus the likelihood that learners pay attention and learn (e.g., Glass & Smith, 1979; Hedges & Stock, 1983). Thus, it would be useful to extend the Sugrue et al. (1999) study with a balanced design that examines small and large classes with videoconferencing delivery and without. The purpose of our study is to examine differences in training outcomes across classroom and videoconferencing classes for learners in classes of various sizes. Videoconferenced classes