Cerro Muriano is a small population centre situated 16 km to the north of the city of Córdoba, between the municipalities of Córdoba and Obejo (Andalusia, Spain). This territory is situated over a large field of copper veins, which has...

moreCerro Muriano is a small population centre situated 16 km to the north of the city of Córdoba, between the municipalities of Córdoba and Obejo (Andalusia, Spain). This territory is situated over a large field of copper veins, which has been exploited by the different peoples and societies that have populated Córdoba’s mountain range Sierra Morena. The mining and metallurgy of this red metal have been used to track the evolution of this site over time. This has produced much archaeological evidence, ranging from the Copper Age to the 20th century. Thanks to its originality and its well-preserved state –and also the commitment of Fernando Penco Valenzuela, the director of the Museo del Cobre (Copper Museum) located there– this particular piece of mining history enjoys legal protection today.

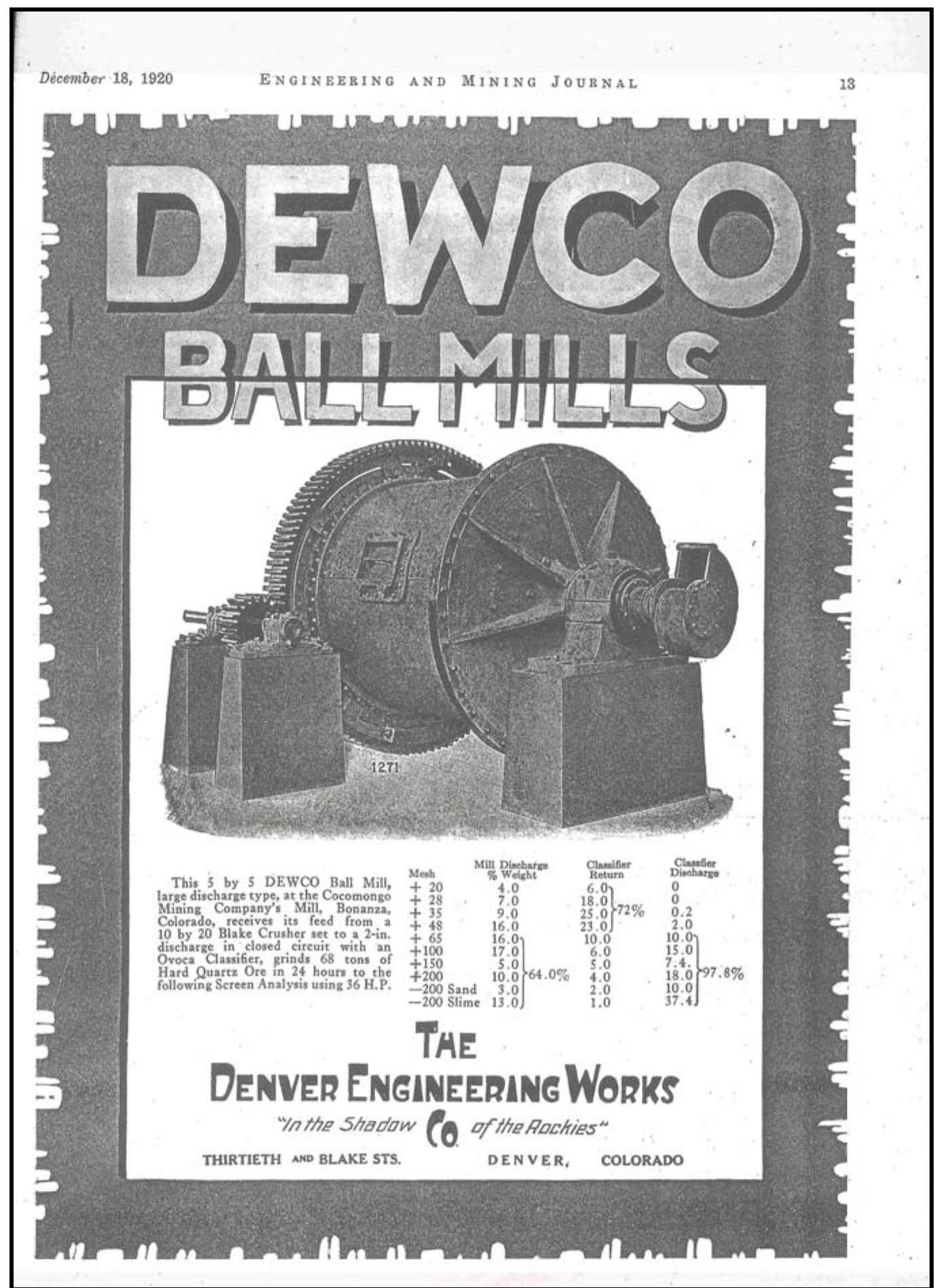

From 1897 to 1919, the mines of Cerro Muriano were worked –with the new technologies brought by industrialisation– by four different, but closely related, English companies: Cordova Exploration Co, Ltd. (1897- 1908), Cerro Muriano Mines, Ltd. (1903-1908), North Cero Muriano Copper Mines, Ltd. (1906-1908) and Cordoba Copper Co., Ltd. (1908-1923). The first of these was from the Newcastle area, and the rest were from London. These companies developed the mines using nine main extraction shafts: Calavera, San Lorenzo, Unión, Excelsior, Santa Victoria, San Rafael, Levante, San Arturo and Santa Isabel; some of these remain while others do not. The separation between the northernmost (Calavera) and the southernmost (San Isabel) shafts is around 2,025m. The distance between the eastern (Unión) and western (San Arturo) extremes is approximately 2,275m. In this territory, the four cited companies generated a complete mining settlement, composed of the above extraction points; a plant of considerable dimensions for washing and concentrating the minerals, calcining them, smelting them, and finally converting the matte into blister copper; and a populated complex of various neighbourhoods composed of houses, shacks and barracks. In addition, there was other infrastructure required to sustain a society (e.g., a school, canteen, theatre, church, hospital, etc.), buildings for work (e.g., offices and a laboratory), and other spaces for production, storage, and distribution.

Communication with the exterior took place through three principal routes demarcating a clear north-south axis: the old road from Córdoba to Almadén (N-432a), the Cañada Real Soriana droveway, and the rail line between Córdoba, Belmez and Almorchón. Along with these routes, there was a dense network of paths and narrow gauge railways throughout the area. It was specifically the train that connected the city of Córdoba with the coal-mining area of Peñarroya-Belmez-Espiel (in the north of the province) that permitted the English to set up their business in a mountainous location that was thus completely dependent on the railway.

At the end of the 19th century, the train did not stop at Cerro Muriano. In fact, there was nothing to motivate the construction of a train station there: neither a consolidated population nor any important economic activity. Thus, one of the primary objectives of the initial English capital investment was to bring the rail line to its properties. Therefore, mining and railways marked the origin of Cerro Muriano as we know it today.

Finally, this study case of Cerro Muriano during the English period found that it was a faithful reflection of its time. Spanish mining in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries was heavily influenced by the involvement of foreign companies. This should not be seen as a distinctive feature of Spain as a whole, but rather as the result of an international situation in which mining underwent a kind of premature globalisation. In view of the foregoing, it may be argued that the British Cerro Muriano was a standard product. In it, we can discern many of the features typical of the international expansion and industrialisation of mining and metallurgy operations: the key introduction of new technology in the exploitation of the mine, the fundamental importance of the railway –even though in Cerro Muriano the line already existed, and was not purpose-built to serve English interests–, the eclectic nature of the whole in terms of the technology employed (particularly American in metallurgy, British and German in mining), and the creation of a mining village, in the town- planning and social senses.

In short, Cerro Muriano is a good example of economically-colonialist mining activity that seems to show that the highly topical subject of globalization is not a new phenomenon, since the evolution of technology and the spread use of the same machines on an international scale –among other circumstances– facilitated the homogenization of the world we inhabit today.