Abstract The Bridegrooms’ Diadem Meir Bar-Ilan This book is dedicated to the study of Jewish wedding of in antiquity from Biblical times till the end of the Talmud era with emphasize on the Rabbinic sources (ca. 1st-6th centuries C.E.)....

moreAbstract

The Bridegrooms’ Diadem

Meir Bar-Ilan

This book is dedicated to the study of Jewish wedding of in antiquity from Biblical times till the end of the Talmud era with emphasize on the Rabbinic sources (ca. 1st-6th centuries C.E.). However, more evidence comes from medieval times as a comparative tool that gives an indispensable viewpoint. Since wedding is a multifarious event it is studied with the help of interdisciplinary methods. First and foremost, the text is analyzed from the literary and philological point of view. Historical, liturgical, sociological and folkloristic aspects are added. Strangely enough, most of the issues discussed herein have not been the subject of critical research until now, including all sorts of lost rituals and customs.

Chapter 1: Wedding-Songs

The aim of this chapter is to draw attention to ancient Jewish wedding-songs, a type of song usually ignored by modern scholars; there are practically no wedding-songs in contemporary Jewish tradition.

The chapter begins with a wedding-song mentioned in the Talmud, continues with one mentioned briefly in the midrash, and goes on to a text preserved in the Hebrew book of Tobit. Additional wedding-songs are dealt with, especially those that seems to be more ancient and do not display marked literary features. Of special interest are wedding-songs from Yemen and Cochin, India. Over 50 songs are discussed in an attempt to understand the special qualities of Jewish wedding-songs in antiquity. A comprehensive bibliography of Jewish wedding-songs in all periods is provided.

Chapter 2: The Seven Wedding Blessings

An integral part of any Jewish wedding is the well-known recital of the seven blessings under the canopy. This chapter seeks to analyze the development and meaning of these blessings.

The main argument is that the sources indicate a development regarding the number of blessings: in the early strata of the liturgy there were people who recited three blessings only. Later these three became four, then five and six. With the additional blessing over the wine, the wedding ceremony reached its present stage, with seven blessings.

The main theme is the form and content of the blessings, with a glance at some marginal features as well. It is shown that the meaning of the blessings is twofold, expressing both Jewish identity of the new couple through ties to family and friends, and the religious credo of their faith.

A special appendix is dedicated to the numerological value of the number seven, trying to explain its meaning as a divine blessing.

Chapter 3: Rejected or Lost Wedding Rituals

This study deals with five different aspects of wedding rituals. The main focus is on virginity and its significance, from Biblical times till the Middle-Ages.

A. According to the Bible (Deut. 22:13-21), a bridegroom may claim that his newly-wed bride was not a virgin at the time of the wedding; if his claim is found to be true – by the test of the blood of virginity on the cloth – the woman is condemned to death. The Tannaim had the same idea of the importance of virginity. Although it is assumed that the practice of displaying the stained cloth had disappeared, it actually prevails to this very day (among some Oriental Jews). In practice, all cases of a groom coming to court claiming that his bride was not a virgin were rejected (indeed, one of the claimants was punished). This change of attitude can perhaps be ascribed to the move of the Jewish people from the cultural influence of the Fertile Crescent region to Mediterranean culture (known later as "Western").

B. A special blessing used to be recited by the groom upon ascertaining the bride's virginity. The blessing is not mentioned in the Talmud, and Maimonides condemned it as immoral; it was subsequently ritually rejected. Some versions of this blessing are discussed, as well as its history.

C. According to the Mishna (Kidushin 1:1), one may “buy” a wife by three different means, one of which is intercourse. This ancient practice was stopped by Rav (3rd c. Babylonia), who ruled that one who wed his wife by intercourse should be whipped. The proof of virginity, the virginity-blessing, and wedding by intercourse are actually different aspects of the same concept: the high value placed on virginity in Jewish culture.

D. The midrash tells a story about the son of R. Aqiba and his bride, who after the wedding studied Torah “all night long”. It is proposed that this story shows that learning Torah in that society was a supreme value.

E. The tractate of Kalla Rabbati tells a story of a bride who commits adultery immediately after her wedding. After many years, this was discovered by R. Aqiba by looking at the woman’s child. It is proposed that this story was told as a kind of hagiography, to show that R. Aqiba had divine powers. It is also suggested that Kalla Rabbati originated from Mehoza and reflects a folk-religion.

Chapter 4: Wedding Stories

This study discusses stories that were told during wedding celebrations among many nations and ends with wedding stories that appear in the Bible.

In the beginning the genre of wedding-story is characterized as a story that was told in a unique occasion, or “Sitz im Leben”, as it is called among Biblical scholars. The first story to be discussed is “The Wedding of Sir Gawain and Dame Ragnelle”, known from the Arthurian legend, a story that exemplify the concept of a wedding-story. The symbols of the story are explained as well as the idea of marrying a monstrous spouse. Several stories from the collection of Grimm Brothers are analyzed showing that they were aimed to be told in wedding occasions.

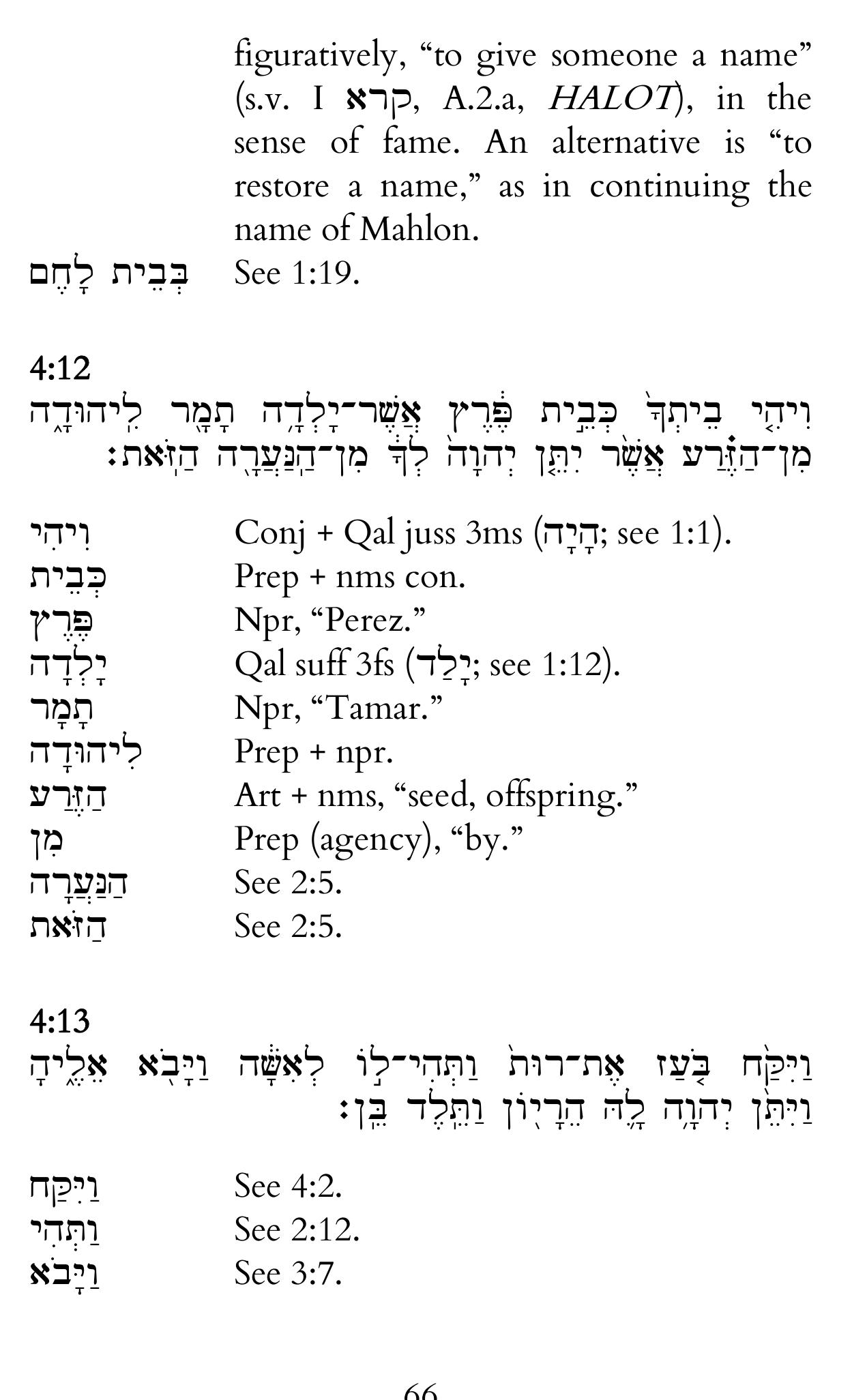

The Book of Tobit, from the Apocrypha, is shown, according its theme and lexicography, to be a wedding story. These different stories have a common denominator with some Biblical stories where the wedding is the climax of the narrative, such as the Scroll of Ruth and the wedding of Rebecca (Genesis 24). It is assumed that these stories, before they were committed to writing they were told in wedding ceremonies and played a role of Bildungsroman. In an appendix a new story is given: “The Wedding of the Daughters of Zelophehad”.

Chapter 5: The Song of Songs as Wedding Songs

This study is part of type-critical (gattungsgeschichtliche) of the Song of Songs. It aims to show that the genre of the Song of Songs is wedding songs. This hypothesis has been already known to scholars for more than 140 years. The evidence was drawn from cultures far distant, in time and in space, and therefore there was no agreement among the scholars whether to accept or reject this hypothesis.

This study is based on a few hundred wedding-songs sung among Jews in more than a millennium (and still a very long time after the biblical text was composed). The reasons supporting the wedding-songs hypothesis are as follows:

1. Content: specific words and motifs in the biblical text. These words are: wedding, bride, love, scents, physical description and breast. Far later Jewish wedding songs also have the same characters of the Biblical text.

2. Form: the dramatic character of the Biblical text is well known and a ‘modern’ song is presented (assumed to be sung in a new baby-girl ceremony). The song has the same concept, that is: mini-drama and duet between the bride and the groom as to make everyone joyful.

3. Use of the text: the idea is that the modern use of a text should be considered while looking for its genre, a concept already used by Mowinckel while analyzing enthronement psalms. According to this idea it is shown that many verses of Song of Songs are sung, until this very day, among Jews at weddings. This use should be taken as an indicator of the original setting of Song of Songs in its Sitz im Leben.

Special discussion is devoted to understanding why the text was understood allegorically and what made its type irrelevant to rabbinic wedding-songs. It is argued that in “Biblical times” the wedding-ceremony used to be part of popular religion and only in later times, under rabbinic movement, did the ceremony become part of the official religion so the text was understood as immodest (and therefore MUST have been created to describe Divine love).

In sum: different data are put forward and the comparison between known wedding songs and Song of Songs leaves no doubt: the Biblical text was originally composed as wedding songs.