Meaning and Narration in Product Design

Sign up for access to the world's latest research

Abstract

Contrary to the belief of the Modern Avant-garde, at present there seems to be an agreement in the design community about the narrative qualities of artefacts. In spite of the undoubted communicative functions of products in the broadest sense, some proponents of product semantics and design semiotics raise objections insofar as "products cannot talk" and that the term "a product tells a story" is an imprecise expression. This paper discusses the appropriateness of terms such as product language, narrative design, etc. It draws on case studies from the area of product design and suggests a distinction between meaning and narration in product design. Furthermore, it differentiates between narration that is embodied in the product itself and narration and stories that are connected with products by users or through marketing.

Related papers

Abstract: The article is about how Product Semantics, as an old paradigm of design, can be reevaluated to have a broader look to include a user-centered approach. In this attempt, a workshop held in ITU, Department of Industrial Design was taken to exemplify the potentials of this new approach. The main focus of this paper is to test the possible extensions of the seven semantic categorization of Burnette (1995) and see how “useful” it is in order first to analyze the users’ connection with their material world; and second, ideate the data gained from this analysis into more concrete design concepts. This was tested in an educational exercise as a controlled practice. This paper presents a small workshop performed together with graduate students of Industrial Design in Istanbul Technical University to see how those possible extensions of methods or approaches can reach the desires, wants, and perspectives of user by using only the main categories that Burnette presented years ago. This exercise tries to transfer an old paradigm of design, Product Semantics, into a new and fresh one with a new look to the users, how they see their material world and how a designer can extract new clues about design with an approach similar to design ethnography. Keywords: Design, product semantics, user-centered design, design education

2018

A particular thank you to my mother, Elaine Luti, who actually read the whole PhD to point out all the grammar problems, colloquialisms, repetitions, and areas that didn't make sense. Only a mother would do that for free! And last but not least thank you to my father Michele and brother Luca, my husband Rob, my daughter Clara who won't remember a time before I was a PhD student, and my son Dario, who was born half way through it, for encouraging me throughout.

Dissertation unit as part of BSc (Hons) at London South Bank University 2003. Dealing with design semiotics, branding and user research. Wth growing globalisation and competition there have been an ever increasing need for corporations, new product development professionals, and especially among designers to develop methods for exploring consumer interaction and behaviour. The methods for this field of consumer research and exploration have many directions such as semiotic approach, pleasure based design, product personality assignment and many other. The common term for all these methods are commonly known as design psychology.

2021

Every design project is the history of a transformation occurring as an answer to a certain need or opportunity. The action of narrating is therefore implicitly (and in some cases also explicitly) present in every design process. The understanding and study of the constituent elements of narration can therefore represent an instrument of conscious appropriation of techniques and methods often enacted in a spontaneous, unconscious, habitual way. Unlike design, a young discipline whose methodological apparatuses still need to be constructed and perfected, narration has a long history. It has seen a rich and articulated decoding process, which has enriched itself from time to time by having crossed the most various fields - from visual art to music, from literature to multimedia. The aim of the present paper is to underline the potential of narrative languages, formal structures and content schemata in the design field, by putting in contact the perspective of the writer-scriptwriter (...

Nowadays the stories of the objects may be as important – if not more – as designs themselves. Observing that conceptual design objects are always accompanied by stories, this thesis investigates how the story mediates between designer, object and viewer. After a vast background research was made into contemporary designs and their stories, the topic was explored through text analyses, a survey and a workshop. Further examined was how the writing of our thesis (the “story”) intervened in the making and in the appreciation of our objects. The relevance of this thesis lies in the fact that, by bringing to light unspoken conventions such as of using the idea of authenticity as a means to give value objects, it offers new perspectives in the relationship between objects and stories.

This paper analyzes the design discourse of product designers and aims to understand the balance between the requirements imposed by the technical rationality and the emotional needs of designers. Eight designers were interviewed and organized in two groups, according to their profiles: experienced and young designers. The results indicate that the relations with the business and the type of experience with product development are more important than the academic background of the designers in their constitution of a design discourse.

This article is a case study of the design and development of a Norwegian crockery series for institutional households - the 1962 Figgjo 3500 Hotel China. It investigates how this product represented a decisive break with the conventions of postwar Norwegian design and manufacture. The onset of international free trade meant export or die for the manufacturing industry. The elitist aestheticism so prevalent in the so-called Scandinavian Design movement was abandoned in favour of an ideology remarkably akin to what was at the German Ulm School of Design called scientific operationalism. The paper also analyses how the manufacturer sought to portray this product: first, it was inscribed as science incarnated, and the material morality reigned supreme. But as society's faith in science took some serious blows in the course of the 1960s and modernist design idioms were partly forsaken in the 1970s, the engineered tableware became the fashioned tableware as trends tamed technology. These translations of technology, design, identity and consumption tell the story of how an artefact is constantly in a state of transformation - on both sides of the factory gate.

2021

This study explores the co-existent nature of emotions and cognition in humans to build and propose a framework that helps correlate ‘likeability’ and ‘sellability’ of a product by introduction of a relatively new term—unique selling factor (USF). The framework runs on context-based logical correlations among its constituents. The aim of this framework is to qualitatively express the emotional characteristics of a product. As emotions work alongside with cognition, the design attributes of the product under the lenses are first analysed as per the three levels of our brain’s processing. Each design feature corresponds to the processing level based on the consumers’ probable preferences to choose that feature in the first place. After this cognitive breakdown, we further diverge the semantic analysis at emotional levels. Each design feature when stated with the consumers’ probable preference and the cognition level involved can now help develop context of the scenario. This context that triangulates the connect between the design feature, consumers’ preference and processing level plays significant role as the backbone of emotionality in the analysis overall. To apply the understanding built, a logical study is done considering a black V-neck T-shirt as the product under the lenses. For this product, we define the likeability, sellability and the unique selling factor. For analysis, we create a feature analysis table that subdivides the product features first, into its design characteristics. Second, against these characteristics are explored the probable reasons the consumer might have had for opting for those characteristics. Third, each reason for the preference for its respective design characteristic is assigned to its corresponding levels of brain processing. Fourth, for the context developed so far, we can assign emotions involved. The co-existence of emotion and cognition paves way for this product-semantic design language. Thus, the framework proposed works evidently on emotion and cognition and helps provide a novel perspective—that of the most significant stakeholder of all—the customer and the peoplewe design for. The framework follows an ecosystemic approach that provides it with appropriate literature and a holistic approach.

Product semantics is well anchored in design fields such as industrial and interface design on the one hand and on the other semiologists, sociologists, socio-psychologists and even anthropologists have been analyzing the semantics of clothing and fashion from the viewpoint of their own disciplines. Nonetheless textile and fashion designers are still educated to design in a rather artistic and intuitive manner. In order to provide a theoretical foundation, that can be applied in textile and fashion design practice and that reflects the concerns of professionals this paper presents a model for description and reflection of product meaning in the fields of clothing and fashion.

MEANING AND NARRATION IN PRODUCT DESIGN

Dagmar Steffen

Lucerne University of Applied Sciences and Arts, Faculty of Design (FED)

dagmar.steffen@hslu.ch

Abstract

Contrary to the belief of the Modern Avant-garde, at present there seems to be an agreement in the design community about the narrative qualities of artefacts. In spite of the undoubted communicative functions of products in the broadest sense, some proponents of product semantics and design semiotics raise objections insofar as “products cannot talk” and that the term “a product tells a story” is an imprecise expression. This paper discusses the appropriateness of terms such as product language, narrative design, etc. It draws on case studies from the area of product design and suggests a distinction between meaning and narration in product design. Furthermore, it differentiates between narration that is embodied in the product itself and narration and stories that are connected with products by users or through marketing.

Keywords: Product Language, Product Semantics, Design Semiotics, Narrative Design

1 INTRODUCTION

The assertion that products of daily use and architecture are able to or should “tell a story” is debatable. In the 1920’s proponents of the Modern Avant-garde would have disagreed, and even today the statement does not meet with design theoretician’s approval, in particular, with proponents of product semantics or design semiotics, of all people. However, the objections brought up today differ from those in the past. According to the rationalistic worldview of the Modern Avant-garde, artifacts products as well as architecture - had to “function” and to “perform.” Thus, the term function was limited to utilitarian ends.

In 1927, the architect Ludwig Hilbersheimer took this view: “The best flat will be one that entirely becomes a utility item. In both building construction and furniture construction the creation of standard types is the goal. When this is reached, furniture will be an indifferent concern, which is given; then they … will be reduced to their intrinsic meaning, to be utility items.” [1] Two years later, the Bauhaus adept Laszlo Moholy Nagy verified: " … our utility items are neither cult objects nor center of meditation. They only have to fulfill their function and range in the surroundings in a useful manner." [2] Artifacts should not evoke attention or affection. They were meant to be functional, objective, restraining, timeless and culturally neutral and should remain in the background. This ideology has had a lasting effect on the design philosophy of successors, for example lecturers and students at the Ulm School of Design. Klaus Krippendorff, a graduate of this school, recalls: “Meaning had no currency in Ulm. (…) Under the aegis of functionalism, artifacts could not be conceived to mean different things in different contexts and for different users without being considered wrong.” [3] Due to this ideology, in Germany until the 1970’s the design discourse and also the requirement specifications in design practice were almost exclusively geared towards criteria such as functionality, ergonomics, and suitability for materials and manufacturing. Meaning, symbolism, the communicative and psychological functions of artifacts were not subjects of discourse - at least not in the design community.

Doubtlessly, already at that time disciplines such as psychology and authors like Roland Barthes and Jean Baudrillard provided a different perspective on artifacts, but in the discourse on design of the 1970ies theses such as “Erweiterter Funktionalismus” (Extended functionalism), “Sinn-liche Funktionen im Design” (Sensual functions in design), and “Theorie der Produktsprache” (Theory of product language) [4] by Jochen Gros were part of a paradigm shift. The term “product language” was meant to be a metaphor for elucidating the too long ignored matter that products as such also must be conceived as means for communication, and knowledge creation in this field was regarded as the

specific design competence. During the next decade, various others approaches to product semantics and design semiotics evolved, for example product semantics by Klaus Krippendorff and Reinhart Butter in the United States [5] and design semiotics by Susann Vihma in Finland [6], to mention just a few. Despite different philosophical backgrounds, they share the view that products are bearers of meaning, beside their utilitarian functions. Thus, product language, product semantics and design semiotics are occupied with the exploration of the meaning of products. To be more precise, they investigate what contents products may communicate, how they do this, what they might mean to whom, and what designers might contribute to this.

Nowadays, discourse on product language, product semantics, design semiotics and narrative design have become ubiquitous. The idea that products “mean” or “tell” something to someone is widely shared in the design community. Thus, Susann Vihma states: “… design can easily be treated as a sort of symbolic system likened to verbal narrative and storytelling. … Many semiotic insights have spread to everyday thinking and statements in mass media. Ordinary design discourse is packed with statements such as, ‘a product tells its story’, ‘a form speaks about cultural identity’, and so on.” [7] All the same, Susann Vihma as well as Klaus Krippendorff have their reservations about this linguistic usage. Vihma considers the use of these linguistic metaphors to be a trap, and she recommends: “Instead, it would be fruitful to conceive of material artifacts as carrying symbolic content as concrete forms in their own right. To conceive material products as visual metaphors can be more beneficial for design theory. Why associate (visual) forms with speech and verbal communication in the first place? It is worthwhile discussing this question because, as can be seen, the answer has consequences with respect to design discourse. Speaking and writing about form become different. Instead of saying ‘a product tells its story’, the statement is made that 'a product expresses (represents, refers to, displays, exhibits, or embodies) a quality for someone. Consequently, it also becomes evident that a form in its material and visual presence always expresses (something to somebody). Signification can be regarded as a relation and interaction between the form and the person who perceives it.” [8] And Klaus Krippendorff explained with respect to the theory of product language: “Products cannot speak a language, humans do.” [9]

2 MEANING IN PRODUCT DESIGN

Without question, products do not themselves speak; they do, however, offer projection surfaces for meaning and they are objects to be interpreted by the beholder. Since there is no single form, so to speak, of a car, but rather many different cars, they provoke symbolization and ascription of content or meaning. Various approaches to product language, product semantics and design semiotics operate with the term “meaning,” and some authors also use the term “message.” [10]

2.1 Discursive and presentational symbolism

Philosopher Susanne Langer argues in her work “Philosophy in a New Key” (1942) that symbolism and meaning can take two modes of expression: discursive forms on the one hand and presentational forms on the other. Discursive symbolism, i.e., verbal language, is characterized by the fact that it must embed meaning in successively strung words, while presentational symbolism - such as works of art, a painting, a photograph, etc. - presents its elements coinstantaneously. Nevertheless, according to Langer, discursive and presentational forms of expression have in common the fact that both are the result of symbolic processes and bearers of meaning. “Visual forms - lines, colors, proportions, etc. are just as capable of articulation, (i.e., of complex combination) as words”, she states. [11] Visual and acoustic sense-data are “par excellence receptacles of meaning”. Thus, the field of semantics is wider than that of language, and the unsayable can be articulated as well. “It is quite natural, therefore, that philosophers who have recognized the symbolical character of so-called ‘sense-data’, especially in their highly developed uses, in science and art, often speak of a ‘language’ of senses, a ‘language’ of musical tones, of colors, and so forth.” [12] This metaphorical phrase also entered the realm of architecture and design, as titles such as “Language of Post-Modern Architecture” or '“Theory of Product Language” prove. [13]

Having said this, in the very next passage Langer warns that such an idiom/ mode of speaking that levels the difference between nonverbal and verbal embodiment of expression is delusive and imprecise. Aside from similarities, she accentuates substantial differences between the two. Langer argues: "Language in the strict sense is essentially discursive; it has permanent units of meaning which are combinable into larger units; it has fixed equivalences that make definition and translation

possible; … In all these salient characters it differs from wordless symbolism, which is non-discursive and untranslatable, does not allow of definitions within its own system, and cannot directly convey generalities." [14] Furthermore, she states that it is impossible to break representational symbolism into pieces. In fact, a representational symbol such as, for example, a painting, consists of elements; but in contrast to language, these elements do not represent units of independent meanings. “We may well pick out some line, say a certain curve, in a picture, which serves to represent one nameable item; but in another place the same curve would have an entirely different meaning. It has no fixed meaning apart from its context.” [15] To summarize, the differences between discursive and presentational symbols pointed out by Langer are on the formal level, and these formal differences at least partly answer the question about how products communicate meaning, in contrast to verbal language: namely, in a presentational mode.

2.2 Cognitive interest and content of meaning

To read and interpret products means to transform their presentational symbolism into a discursive symbolism - at least, as far as this is possible. Here, I argue that this transformation is based on an invariant, i.e., the object, but also on variables: first, the context in which the object is placed, and second, the epistemological or cognitive interest of the interpreter. Thus, the interpretation of one and the same object can vary significantly.

An object-side meaning depends on the sensuous appearance and utilitarian functions of the object, that is the design of form, color, surface, material, manufacturing technique and quality, functionality and usability and, last but not least, the relationship between means and ends that is embodied in the artifact. For example, in daily life a mink coat can be interpreted both as a warm winter coat and a politically incorrect status symbol. This interpretation derives from the physical capacity/ the nature of the material to keep somebody warm, its rarity and high price and animal rights campaigns. Hence, the scope of interpretation is not arbitrary.

Furthermore, the meaning depends on the particular context. One and the same object may carry different meanings according to the temporal and spatial context. For example, the Wassily Chair designed by Marcel Breuer at the Bauhaus in 1925/ 26 was meant to be a highly functional, convenient and cheap utility item for mass production and mass consumption. In an essay, Breuer elucidated the constraints and argued that form, material and construction were deduced from them in a rational manner. Nonetheless, both in the 1920’s and from the 1980’s onward, the connotations of the object were in strong contrast to the intentions. In the 1920’s the chair was a symbol of modernity, progress and open-mindedness for the cultural elite, and in the 1980’s the seat turned into a so-called “modern classic”, a celebrated and unassailable object, having an aura of the “golden age” of modernism about itself. This symbolic meaning was reinforced by countless publications and museum exhibitions. [16] Finally, on the subject-side the interpretation of the artifact will be influenced by social background, age, gender, experience, political and philosophical attitude, values and life-style of the beholder. The choice of ones clothing, accessories and products does not depend only on functionality and price but also on the meaning and associations they evoke in the eyes of the beholder. If the artifact is investigated with scientific interest, the existing theories and theses of the discipline will guide the interpretation. These factors constitute the “lens” through which the interpreter examines and construes the object.

For example, in his work “The Adventure Society” (“Die Erlebnisgesellschaft”) Gerhard Schulze interpreted material culture respectively products from the point of view of cultural sociology. His scientific interest was driven by the question about what products reveal and whether they would verify his hypotheses on Western culture at the end of the 20th century. Thus, in the introduction to his work he argues about cross-country vehicles with chrome-plated buffer-bars and durable footwear made from delicate buckskin. He reasons that the practical value of those products gave way to turning them into experiences; their robustness became an aesthetic attribute. In other words, Schulze interprets characteristics of the material culture as symptoms of the mental values of the society that designs, produces and uses these artifacts. He infers: “All of this aestheticization and pseudoaestheticization of products is part of an all-embracing change that is not limited to the market of commodities and services. Life, per se, turned into an adventure project.” [17]

I suggest, that these interpretations of artifacts offered by other disciplines bear relevant insights for design research and for design practice as well. Nevertheless, from my point of view design has a specific interest and approach in its own right when it comes to the interpretation of designed artifacts.

The Offenbach approach of a theory of product language identifies this epistemological interest in the relationship between artistic means (such as form, color, surface and materials) and their impact and meaning on the beholder. In other words, from the perspective of design practice it is important to gain some understanding/ insight about which artistic means might evoke what associations and meanings at a certain time for a certain target group in order to design artifacts in such a way that they are an adequate projection surface for beholders.

2.3 The Offenbach School approach to product language

Interpreting products also means reading signs. Following up on the distinction between sign (signal) and symbol introduced by Susanne Langer in the aforementioned work, the theory of product language differentiates the semantic product functions into sign resp. indication functions on the one hand, and symbolic functions on the other. [18] Indication functions are directly related to the product and reconcile technique and human beings. They enable the nature of a product or the product category to be identified. Furthermore, they visualize and explain the various practical functions of a product and how it should be used. For example, configuration and shape of indication signs visually define the product category and the product’s functions; the form of a knob indicates whether it is a pushbutton or a turning knob, etc.

Distinct from indication signs, symbols are associated with objects in the imagination of the recipient or user. While there exist various concepts and definitions of the term “symbol” in history, the theory of product language refers to the related concepts of Susanne Langer, Rudolf Arnheim and the psychoanalyst Alfred Lorenzer. According to them, the meaning of symbols includes denotations as well as connotations. Thus, the symbol functions refer to conceptions and associations that come to a persons mind while contemplating an object, i.e., societal, socio-cultural, historical, technological, economical and ecological aspects. They convey conceptions of a period style, various partial styles or typical users. For example, a certain coffee set might evoke thoughts about the 1950’s, other characteristic products, fashion and music from that era. A Montblanc fountain pen might be associated with stereotypical users, i.e., a certain target group and values such as performance and leadership, status-consciousness, exclusive taste and a conservative lifestyle. Last but not least, associations like those that constitute a semantic differential (female/ male, soberly/ cheerful, exciting/ boring, etc.) are part of the symbolic aspects of products. Considering these contents and meanings, formulations such as “color and shape indicate that …”, “the product symbolizes for me…”, “it connotes …” are more pertinent than "the product tells … ". Meaning results from an object-subject relation, it is not a property of the object.

3 NARRATION IN PRODUCT DESIGN

Meaning, at least in the presentational form it takes in product design, is not synonymous with narration. According to Helene Karmasin, narration represents “a particular type of syntactical interconnection”. In order to identify a narrative structure, at least two states linked with each other and an intermediary event must be given: “State 1 and state 2 are interconnected in such a way that state 2 emerges (occurs) from state 1, causally originated by a transformation or an event.” Consequently, the underlying pattern of a narration is as follows: “State 1: Hans is poor. Event: Hans plays the lottery and wins. State 2: Hans is wealthy.” [19]

This structure is widely used in advertising films. However, the question is whether products can embody or symbolize a temporal sequence as well. Evidently, the meaning of products is not necessarily a “story” or a “narration” insofar as the presentational symbolism that characterizes products can represent such a time-based narrative structure in an indirect manner at most. Two strategies for such an indirect representation of a narration are conceivable even if they might coincide in some cases. The first strategy concerns the materiality of a product; the second is related to an intervention of the user-co-designer.

3.1 Narration of materiality

The materiality of a product may point to a state 1 before the intermediary event takes place, and a state 2 afterwards. Products that consist of nearly untreated natural material, ready-mades or recycled material show this in a rather obvious way. A piece of furniture like, for example, a writing table exhibiting a crotch, designed by the German artist group Rotes Haus, or the deer head furniture designed by Uwe van Afferden in 1985 indicate without ambiguity the derivation of the material.

(Figure 1) In contrast to products made out of homogeneous materials such as plastics, MDF (medium density fiberboard) or glass, the aforementioned products show an iconic reference to the raw material from which they are crafted. Thus, metaphorically speaking, one might say that these products in their instant state 2 narrate or tell about the former state 1 and the transforming event in between. They indicate what they were as well as the transforming design and production process.

Figure 1. Writing table, Rotes Haus, 1970s

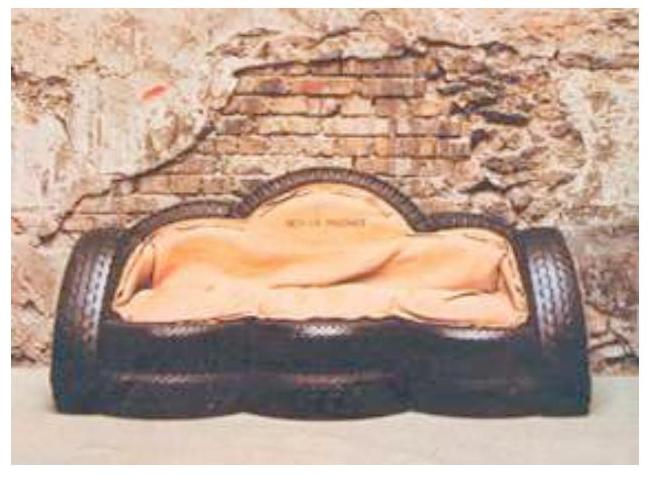

A “before” and “afterward” is also captured in products made out of recycled material - for example those by the Offenbach based so-called design initiative Des-In in the middle of the 1970’s. Facing the environmental problems described in the Meadows report “The Limits of Growth,” they created products such as a tire-sofa, furniture, lampshades and briefcases and pieces of jewelry. The previous history and the origin of the recycled material - the car tires, the offset printing plates, the overseas shipping tea chests and the parts of clockworks - become apparent. (Figure 2) The very same design strategy was pursued by the Dutch group Droog Design, as, for example, the “Chest of Drawers” or the “Rag Chair” designed by Tejo Remy prove.

Elapsing / Passing of time and alteration of products during use is also reflected in a patina or signs of repair. Hints of usage that became inscribed in the formerly virgin, brand new product indicate a longer or shorter useful life, thorough maintenance or inappropriate treatment. This type of unspectacular narration, which comes apparent by taking a close look at the materiality of a product, can be related to the indication functions.

Figure 2. Tire-sofa, Des-In/ Jochen Gros, 1974

3.2 Narration of user-co-design

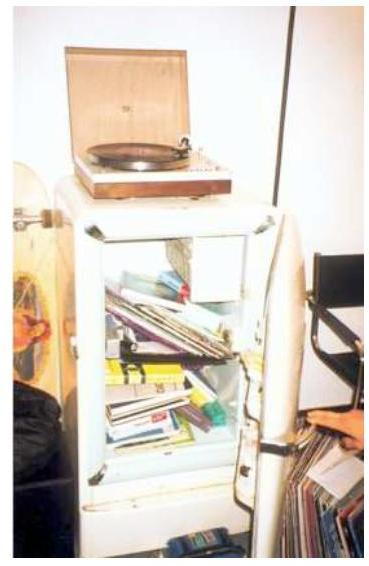

Slightly different from narration inscribed in materials are those that happen when users give new functions or meanings to products. Kristina Niedderer [20] describes this phenomenon as “inventive use,” while Uta Brandes and Michael Erlhoff [21] call it “Non Intentional Design” (NID). A photo collection presented by Brandes and Erlhoff proves that the practical functions of products that are

primarily intended by the designer are widely ignored by users. They “misuse” an empty wine bottle as flower vase, an old fridge as bookcase, and so on. (Figure 3) This is a commonplace phenomenon. From the perspective of the theory of product language, it can be described as a creative and true reinterpretation of indication signs by users. But this non-intended change of use does not mean that users failed to comprehend the intended function and meaning. Latently it exists, but it is suspended.

Figure 3. NID of an old fridge

Intellectually more demanding than the rather mundane reinterpretation of indication signs are transformative interferences on the level of symbols, since those courses of action operate on the level of values. Strategies such as culture jamming, brand hacking and adbusters belong to this approach since they suspend the symbolic meaning of brands or products, reassess common values and suggest a subversive new interpretation. Examples are the American flag, with logos of powerful companies such as McDonalds, IBM, Coca Cola, Camel, etc. replacing the 50 stars that represent the states; or, to mention another example, the wordplay excogitated by environmentalists who changed the company name Shell into “hell”. (Figure 4) The success of these strategies depends on the fact that the primal/ original meaning of the symbol is still present and recognizable in the re-interpretation but and at the same time overlaid and revered by a new meaning or message. In contrast to the American flag or the company name Shell, which have a definite and one-dimensional meaning, the re-design refers to a state 1 and a transformative event. In other words, it possesses/ exhibits a narrative structure waiting to be explored and interpreted by the beholder.

Figure 4. Adbusters: Reinterpretation of the American flag

The debate incited by Susann Vihma and Klaus Krippendorff as to whether the material and visual presence of products might “express” “embody” or “symbolize” something for someone or whether they are able to “tell a story” might be resolved by the distinction between meaning and narration. If the expression “a product tells its story” is to be more than a vague and criticizable term, products have to exhibit a surplus that exceeds the dimension of meaning. They have to show signs that allow

conclusions about a temporal progression and a transformative event. Products that are narrative in this sense might be more rare than those that mean or embody something. Furthermore, as well as meaning, narration is a result of an object-subject-relationship, not a property of the object.

4 NARRATION ATTACHED TO PRODUCTS

In contrast to a narration embodied in the product itself, narrations attached to products are very common. Users as well as companies associate stories with products, but the intents differ. Stories that were concatenated with a certain product by users are prevalently part of his or her history and selfimage. The object might be a family heirloom that brings back memories of one’s ancestors; it might be a souvenir that holds memories of a journey and particular adventures; it might be a gift from a special friend or from a momentous event, or it might be a comprehensively selected object that answers certain idiosyncrasies. If asked, the owner will be prepared to tell a story about the object, how, when and where he or she acquired it, what is special about it, what it means to him or her, what the benefits and drawbacks in comparison to other objects are, and so on. Research in this realm is undertaken by various disciplines [22], and Donald Norman puts it succinctly: “A favorite object is a symbol, setting up a positive frame of mind, a reminder of pleasant memories, or sometimes an expression of one’s self. And this object always has a story, a remembrance …” [23] From a design perspective, it is surprising, that the design of the object often has no or rather little influence on its status as a beloved object. Nonetheless, the history of and stories about objects have a reputation of contributing to the longevity of objects. [24]

While in private life stories seem to arise out of a situation quite naturally, narration constituted by companies or institutions is predominantly characterized and motivated by rational elements and a marketing plan. Starting from the UK in the 1980’s, “storytelling” became a popular method for companies to communicate with customers. One became aware of the fact that narration is able to give the audience an understanding of a company’s history, a brand, a product or a service. Furthermore, it is an effective instrument for getting even complex content across in a plain and memorable manner and to create an intense emotional reaction. A successful story might even become a myth; it establishes order and puts everything into a context. [25]

All these virtues might have been the impetus for the German automaker Volkswagen to plan and construct the so-called “Transparent Factory” (Gläserne Manufaktur) in a prime location in Dresden next to the park “Grosser Garten”. In 2002 the company began assembling luxury cars in the facility, and customers have the opportunity to experience a unique adventure. The setting differs totally from common images of factories. There is no noise, no dirt, no smells; the customer can take a seat situated on the assembly line next to his or her future “Phaeton” sedan and watch the factory workers dressed in white overalls. In additional to visiting the factory, they are invited to visit the Semperopera, the Frauenkirche, and to stay in the Taschenberg-Palais, one of the best hotels in town. Thus, car production is enhanced to the point of being a cultural event, and architect Gunter Henn entitles the factory buildings the “Zwinger Palace of the 21st century”. (Fig. 5)

Figure 5. Zwinger Palace, Phaeton sedan, Transparent Factory in Dresden

The underlying intent of the stage and the staging is obvious. The visit is intended to be an unforgettable experience and a subject for narration and even debate. Indeed, it was widely covered in the mainstream media and occasionally a German TV station produces a philosophical panel discussion in the Transparent Factory, “Das philosophische Quartett” (The Philosophical Quartet). [26] Nonetheless, the sale-figures of “Phaeton” lag behind expectations. A crucial point might be whether the narration of luxury and high culture matches the identity of the company Volkswagen (literally “people’s car”); furthermore, the intent to elicit affection and appetite for products may no longer be relevant today.

Designer Kenya Hara reports on the strategy of the Japanese retailer Muji: “As a brand, Muji has neither striking idiosyncrasies nor specific aesthetics. We don’t want to be the thing that kindles or incites intense appetite, causing outbursts like, ‘This is what I really want’ or ‘I simply must have this’. If most brands are after that, Muji should be after its opposite. We want to give customers the kind of satisfaction that comes out as ‘This will do,’ not ‘This is what I want’. It’s not appetite, but acceptance.” And he justifies this attitude: “I wonder if humankind, having rushed after desire, has finally reached an impasse.” [27] The conception “this will do” sounds like a reincarnation of the vision of “indifferent utility items” striven for by modernists Ludwig Hilberseimer and Laszlo Moholy Nagy in the 1920ies. However, nowadays the concept “this will do” is just another story attached to the Muji brand.

REFERENCES

[1] Hilberseimer, L. Die Wohnung als Gebrauchsgegenstand, In: Bau und Wohnung, 1927 (Stuttgart), Reprint in: Zwischen Kunst und Industrie, der Deutsche Werkbund, Ed. Die Neue Sammlung München, 1987, (Stuttgart).

[2] Moholy-Nagy, Laszlo (1929): auf allen gebieten, In: Bauhausbücher 14, Von Material zu Architektur, 1929, Reprint in: form + zweck, Fachzeitschrift für industrielle Formgestaltung, Vol. 3/ 1979, p. 26-27.

[3] Krippendorff K. The Semantic Turn, A new Foundation for Design. 2006 (Boca Raton, London, New York). p. 313.

[4] Gros J. Erweiterter Funktionalismus und empirische Ästhetik. 1973 (Diploma thesis Hochschule für Bildende Künste Braunschweig, Abteilung für Experimentelle Umweltgestaltung.).

Gros J. Sinn-liche Funktionen im Design. form, Zeitschrift für Gestaltung. No. 74, 1976, pp. 6-9, and No. 75, 1976, pp. 12-16.

Gros J. Grundlagen einer Theorie der Produktsprache, 1983 (Ed. Academy of Art and Design Offenbach).

Gros J. Progress through Product Language. Innovation. The Journal of the Industrial Design Society of America 1984, pp. 10-11. (Special Issue, The Semantics of Form).

[5] Krippendorff, K. and Butter, R. Product Semantics. Exploring the Symbolic Qualities of Form, Innovation. The Journal of the Industrial Design Society of America 1984 (Special Issue, The Semantics of Form).

[6] Krippendorff K. The Semantic Turn, A new Foundation for Design. 2006 (Boca Raton, London, New York). p. 293.

[7] Vihma S. Design Semiotics - Institutional experiences and an initiative for a semiotic theory of form. In Michel R. (Ed.): Design Research Now. Essays and selected projects. 2007, pp. 219 232. (Birkhauser Basel, Boston, Berlin). Here p. 224.

[8] Ibid p. 225.

[9] Krippendorff K. The Semantic Turn, A new Foundation for Design. 2006 (Boca Raton, London, New York). p. 293.

[10] Karmasin H. Produkte als Botschaften, Was macht Produkte einzigartig und unverwechselbar? 1993 (Ueberreuter Vienna). See also: Bausinger, H. Die Botschaft der Dinge. In: Kallinich J. and Bretthauer B. (Ed.), Botschaft der Dinge. 2003 (Edition Braus Heidelberg), (Exhibition catalogue Museum of Communication Berlin), pp. 10-12.

[11] Langer S.K. Philosophy in a New Key. A Study in the Symbolism of Reason, Rite, and Art. 1957 (Cambridge, Harvard University Press).

[12] Ibid p. 93-94.

[13] Jencks Ch. Language of Post-modern Architecture. (Academy Edition, London 1977).

[14] Langer S.K. See footnote [11] ibid p. 96-97.

[15] Ibid p. 95.

[16] Breuer G. Die Erfindung des Modernen Klassikers. Avantgarde und ewige Aktualität. 2001 (Hatje Cantz, Ostfildern-Ruit).

[17] Schulze G. Die Erlebnisgesellschaft, Kultursoziologie der Gegenwart. 1992 (Campus, Frankfurt am Main).

[18] Gros, J. Grundlagen einer Theorie der Produktsprache, Symbolfunktionen, 1987 (Ed. Academy of Art and Design Offenbach).

Fischer R. and Mikosch G. Grundlagen einer Theorie der Produktsprache, Anzeichenfunktionen, 1984 (Ed. Academy of Art and Design Offenbach).

Steffen, D. On A Theory of Product Language, formdiskurs, Journal of Design and Design Theory, No. 3, 1997, 3, 16-27.

Steffen D. Design als Produktsprache, Der Offenbacher Ansatz in Theorie und Praxis, 2000 (Form, Frankfurt am Main).

[19] Karmasin H. Produkte als Botschaften, Was macht Produkte einzigartig und unverwechselbar? 1993 (Ueberreuter, Vienna).

[20] Niedderer K. Designing the Performative Object: a study in designing mindful interaction through artifacts. 2004 (Thesis submitted to the University of Plymouth, Falmouth College of Arts)

[21] Brandes, U., Erlhoff M. and Wagner I. Non Intentional Design. 2006 (daab, Cologne, London, New York).

[22] Selle, G. and Boehe J. Leben mit den schönen Dingen. Anpassung und Eigensinn im Alltag des Wohnens. 1986 (Rowohlt, Reinbek bei Hamburg).

Csikszentmihalyi M and Rochberg-Halton E. The Meaning of Things. Domestic symbols and the self. 1981 (Cambridge University Press, Cambridge).

Habermas T. Geliebte Objekte. Symbole und Instrumente der Identitätsbildung. 1999 (Suhrkamp, Frankfurt am Main).

[23] Norman, D. Emotional Design. Why we love (or hate) everyday things. 2005 (Basic Books, New York) Here p.6.

[24] Deutsch Ch. Abschied vom Wegwerfprinzip: die Wende zur Langlebigkeit in der industriellen Prodution. 1994 (Schäffer-Poeschel, Stuttgart).

[25] Spath, Ch. and Foerg B.G. Storytelling & Marketing, 2006 (Echomedia, Vienna).

[26] See for example: Rauterberg, H. Glaube, Liebe, Auspuff, Die Zeit 1999 (2.9.1999)

Rauterberg, H. Ganz grosse Fragen am Fliessband, Die Zeit, 2001 (No. 51, 13.12.2001).

Rauterberg. H. Selbst die Gegenwart ist bereits eingefroren, Die Zeit 2002 (No. 37, 5.9.2002)

Lampeter, D.H. Kraftakt in Wolfsburg, Die Zeit, 2004 (No. 39, 16.9.2004)

[27] Hara, K. Designing Design. 2007 (Lars Müller Publisher, Baden). Here p. 238f.

References (33)

- Hilberseimer, L. Die Wohnung als Gebrauchsgegenstand, In: Bau und Wohnung, 1927 (Stuttgart), Reprint in: Zwischen Kunst und Industrie, der Deutsche Werkbund, Ed. Die Neue Sammlung München, 1987, (Stuttgart).

- Moholy-Nagy, Laszlo (1929): auf allen gebieten, In: Bauhausbücher 14, Von Material zu Architektur, 1929, Reprint in: form + zweck, Fachzeitschrift für industrielle Formgestaltung, Vol. 3/ 1979, p. 26-27.

- Krippendorff K. The Semantic Turn, A new Foundation for Design. 2006 (Boca Raton, London, New York). p. 313.

- Gros J. Erweiterter Funktionalismus und empirische Ästhetik. 1973 (Diploma thesis Hochschule für Bildende Künste Braunschweig, Abteilung für Experimentelle Umweltgestaltung.).

- Gros J. Sinn-liche Funktionen im Design. form, Zeitschrift für Gestaltung. No. 74, 1976, pp. 6-9, and No. 75, 1976, pp. 12-16.

- Gros J. Grundlagen einer Theorie der Produktsprache, 1983 (Ed. Academy of Art and Design Offenbach).

- Gros J. Progress through Product Language. Innovation. The Journal of the Industrial Design Society of America 1984, pp. 10-11. (Special Issue, The Semantics of Form).

- Krippendorff, K. and Butter, R. Product Semantics. Exploring the Symbolic Qualities of Form, Innovation. The Journal of the Industrial Design Society of America 1984 (Special Issue, The Semantics of Form).

- Krippendorff K. The Semantic Turn, A new Foundation for Design. 2006 (Boca Raton, London, New York). p. 293.

- Vihma S. Design Semiotics -Institutional experiences and an initiative for a semiotic theory of form. In Michel R. (Ed.): Design Research Now. Essays and selected projects. 2007, pp. 219 - 232. (Birkhauser Basel, Boston, Berlin). Here p. 224.

- Krippendorff K. The Semantic Turn, A new Foundation for Design. 2006 (Boca Raton, London, New York). p. 293.

- Karmasin H. Produkte als Botschaften, Was macht Produkte einzigartig und unverwechselbar? 1993 (Ueberreuter Vienna). See also: Bausinger, H. Die Botschaft der Dinge. In: Kallinich J. and Bretthauer B. (Ed.), Botschaft der Dinge. 2003 (Edition Braus Heidelberg), (Exhibition catalogue Museum of Communication Berlin), pp. 10-12.

- Langer S.K. Philosophy in a New Key. A Study in the Symbolism of Reason, Rite, and Art. 1957 (Cambridge, Harvard University Press).

- Jencks Ch. Language of Post-modern Architecture. (Academy Edition, London 1977).

- Langer S.K. See footnote [11] ibid p. 96-97.

- Breuer G. Die Erfindung des Modernen Klassikers. Avantgarde und ewige Aktualität. 2001 (Hatje Cantz, Ostfildern-Ruit).

- Schulze G. Die Erlebnisgesellschaft, Kultursoziologie der Gegenwart. 1992 (Campus, Frankfurt am Main).

- Gros, J. Grundlagen einer Theorie der Produktsprache, Symbolfunktionen, 1987 (Ed. Academy of Art and Design Offenbach).

- Fischer R. and Mikosch G. Grundlagen einer Theorie der Produktsprache, Anzeichenfunktionen, 1984 (Ed. Academy of Art and Design Offenbach).

- Steffen, D. On A Theory of Product Language, formdiskurs, Journal of Design and Design Theory, No. 3, 1997, 3, 16-27.

- Steffen D. Design als Produktsprache, Der Offenbacher Ansatz in Theorie und Praxis, 2000 (Form, Frankfurt am Main).

- Karmasin H. Produkte als Botschaften, Was macht Produkte einzigartig und unverwechselbar? 1993 (Ueberreuter, Vienna).

- Niedderer K. Designing the Performative Object: a study in designing mindful interaction through artifacts. 2004 (Thesis submitted to the University of Plymouth, Falmouth College of Arts)

- Brandes, U., Erlhoff M. and Wagner I. Non Intentional Design. 2006 (daab, Cologne, London, New York).

- Selle, G. and Boehe J. Leben mit den schönen Dingen. Anpassung und Eigensinn im Alltag des Wohnens. 1986 (Rowohlt, Reinbek bei Hamburg).

- Csikszentmihalyi M and Rochberg-Halton E. The Meaning of Things. Domestic symbols and the self. 1981 (Cambridge University Press, Cambridge).

- Habermas T. Geliebte Objekte. Symbole und Instrumente der Identitätsbildung. 1999 (Suhrkamp, Frankfurt am Main).

- Norman, D. Emotional Design. Why we love (or hate) everyday things. 2005 (Basic Books, New York) Here p.6.

- Deutsch Ch. Abschied vom Wegwerfprinzip: die Wende zur Langlebigkeit in der industriellen Prodution. 1994 (Schäffer-Poeschel, Stuttgart).

- Spath, Ch. and Foerg B.G. Storytelling & Marketing, 2006 (Echomedia, Vienna).

- See for example: Rauterberg, H. Glaube, Liebe, Auspuff, Die Zeit 1999 (2.9.1999) Rauterberg, H. Ganz grosse Fragen am Fliessband, Die Zeit, 2001 (No. 51, 13.12.2001). Rauterberg. H. Selbst die Gegenwart ist bereits eingefroren, Die Zeit 2002 (No. 37, 5.9.2002)

- Lampeter, D.H. Kraftakt in Wolfsburg, Die Zeit, 2004 (No. 39, 16.9.2004)

- Hara, K. Designing Design. 2007 (Lars Müller Publisher, Baden). Here p. 238f.

Dagmar Steffen

Dagmar Steffen