Japan-ness in Architecture - Edited by Arata Isozaki

2007, Journal of Architectural Education

https://doi.org/10.1111/J.1531-314X.2007.00152.X…

2 pages

1 file

Sign up for access to the world's latest research

Abstract

AI

AI

Exploring the complexities of 'Japan-ness' in architecture, Arata Isozaki's work analyzes the interplay between traditional and modern influences over a century of architectural development in Japan. It critiques the longstanding notions of minimalism and presents insights into Japanese identity amidst global architectural trends, exemplifying this through historical figures such as monk Chogen and architectural movements like Metabolism.

Related papers

SAJ. Serbian architectural journal, 2014

After mastering Western architecture in the 1910s, Japanese top architects have been confronted with two problems: creating their own style based on Japanese traditions and climatic or seismological conditions and educating common people on taste for architecture beyond superficial imitation of the Western one. First of all, an elite and initially expressionist architect Horiguchi Sutemi discussed non-urban-ness that connects Japanese tearooms and Dutch rural houses. This was through his modernist interpretation of function, his experience in the Netherlands and his reaction against the administrative viewpoints on city and architecture in the 1920s. Secondly, despite his former distant stance on monumentality, his request of the world-wide supreme expression to some projected monuments revitalized his own inclination. Seemingly his attitudes toward monumentality changed and the property of the monuments that honored the war victims or enhanced national prestige opposed the "international" feature of modern architecture. Although these points may hide his consistency, we can find his continuous dualism: one is the functionality that prevailed over architectural discourses at that time including Horiguchi himself and another is his expression that provided a local vernacular practice with the position in the world. These arguments enable us to cast a potential understanding among modern architects in those days in a new light.

Serbian Architecture Journal , 2022

Ranko Radović (Podgorica, 1935 – Belgrade, 2005) was one of Yugoslavia’s most notable architects, urbanists and professors, with a prominent influence on global scholarly discussions on contemporary architecture, urban planning and design. Radović was primarily active in European countries through his practice and academic career. Additionally, he was a council member of the International Union of Architects (UIA) and a President of the International Federation of Housing and Planning (IHFP). In 2002 he became a Minister for Urban Development and Environmental Protection of Montenegro. In addition to his academic role in several countries in Europe, in Japan, Radović was a Professor at the University of Tsukuba and a Guest Professor at the University of Iwate. This paper seeks to show and discuss how his research related to Japan, from his first visit in 1970 to his engagement in academia in the 1990s, shaped how he perceived the concepts of tradition and historicity in Japan’s contemporary architecture and cities. In addition to his articles on Japan for journals, a Serbian publisher in 2004 announced the pre-sale of Radović’s book “Architecture of Japan – dialogue between tradition and modernity” - Radović died before submitting the writing to the publisher.

Published by: Association for Asian Studies Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/20203458 Accessed: 25-01-2018 16:54 UTC

Ever since the opening of Japan in 1853, the archipelago’s pre-modern wooden architecture has fascinated Western designers. The British architect Josiah Conder (1852–1920) was hired as architecture professor at Tōkyō Kōbu Daigakkō Imperial College from 1876 until 1884. He identified this architecture’s specificities and opened the way to a Japanese modern architecture with his pioneering teaching, writings and realisations. The cultural collision with the West and the modernisation process lead thus in the first place to a creative period of selection and assimilation of these Japanese pre-modern architecture specificities – balanced consonance of ornamentation, miniaturisation, asymmetry, performative design and indirect light. We discuss here four major levels defining this assimilation’s process: replication, citation, adaptation and abstraction. Architectural creations born from Japanese architecture and art’s revelation include a range spanning from borrowed elements typical of Japonisme, to abstract designs erasing the original source of inspiration.

Conference proceedings, "Why Does Modernism Refuse to Die?", 2002

Any discussion of the survival and re-birth of Modern architecture begs the question “what is Modernism?”, a question problematic enough in itself. Yet when we consider Modernism’s pervasiveness in non-Western countries the question becomes much more challenging. It demands consideration of its social corollary: the more fundamental query of “what is Modernity?” This paper will attempt to illustrate, with reference to traditional and contemporary Japanese architecture, how a number of qualities of Japanese society and culture problematize our definitions of these terms. A rethinking of our preconceptions of Modernity and Modernism can suggest how it might be that Modernism is still with us when so many of the values on which it is based – values of Modernity – have been called into question.

This paper defines the sense of nature for Japanese culture according to the interpretation of the philosopher Testuro Watsuji, provides an overview of the devices of traditional Japanese spatiality and shows through a critical analysis of various projects by Ryue Nishiwaza, Kengo Kuma and Suo Fujimoto as Japanese contemporary architecture has renewed its bond with nature. The results show a real interest in integrating nature into architectural design reflection and several strategies to do so.

This paper focuses on important architecture events from 1955 to 1970 when Japan started to ameliorate its situation and stabilized its position among developed countries. During this time numerous international seminars, conference, exposition and one Olympic game held in Japan, which gathered many people from all over the world together. Furthermore, new approaches and styles in architecture like Metabolist were introduced from Japanese architecture to the world. All of these was the main reason for Japan to improve its infrastructure, which massively damaged during the World War II. In addition, great architects such as Kenzo Tange played a key role in this improvement through years by designing, constructing and leading great projects, which influenced Japanese architecture and culture.

The author examines architectural theories that led to the founding of Bunriha Kenchiku Kai (Secessionist Architectural Group) in 1920, in line with four phases focusing on the under-standings of “expression”. First of all, the notion of architecture was divided into “art” and “science/utility” when it was introduced to Japan from the West. Secondly, the “art” was relegated to a lower importance through Sano Toshikata's nationalistic view of architecture. Sano's follower Noda Toshihiko subordinated architectural design only to the theory of struc-tural mechanics. Their understandings of “expression” were unilinear. Thirdly, Goto Keiji, Noda's adversary in study, believed that principles of architectural design were to be re-discovered within architects' selves: he became an predecessor of Bunriha. Moreover, a Bunriha architect Horiguchi Sutemi insisted on “life” and “faith” within one's instinct. But their discussions deemed architecture only as reflections of th...

Philosophy East and West, Project MUSE, 2022

The aesthetic comprehension of space is a process of transforming the user into an experiencer and narrator. In Japanese architecture, spatial narration is a method of constructing a bridge between the experiencer and space. This article examines the role of spatial narration as a design tool for spatial atmosphere by considering two acclaimed projects of contemporary Japanese architecture.

Paper presented at APSTSN Conference, NUS Singapore , 2013

This is a paper analyzing how a number of Japanese avant-garde architects, such as Toyo Ito, SANAA, Kengo Kuma and others understand the meaning of"environment" when they design the buildings. Three models of their conceptual framework, namely, co-construction, fractals and being out there, are proposed.

Reviews | Documents

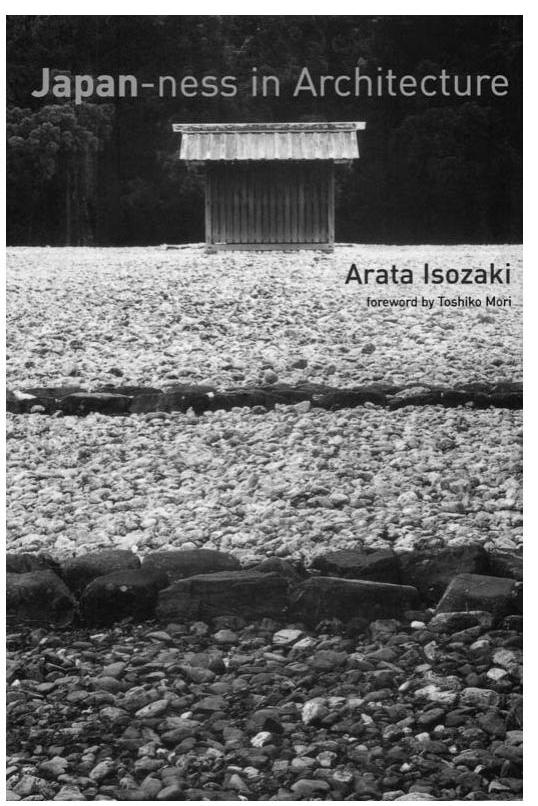

Japan-ness in Architecture

ARATA ISOZAKI

MIT Press, 2006

350 pages, illustrated

$29.95 (cloth)

Since its opening to the world after centuries of self-imposed isolation, Japanese architecture has been subject to a two-sided dialectic. From the EuroAmerican curiosity with Japanese exotica in the mid-nineteenth century to Japan’s willful embrace of Western styles in the thirties; from Bruno Taut’s 1933 proclamation of the Ise shrine and Katsura Villa as the ultimate Japanese archetypes to Kenzo Tange and Yasuhiro Ishimoto’s 1960 documentation of the same villa as a series of Mondrianesque compositions; and

from Metabolism’s capsule towers to Tokyo’s Disneyland, both Japanese and Western architects havewith equal narcissism - concocted the complex and contradictory Japanese architectural scene we encounter today. Despite this century of cross-cultural encounters, the premise of what constitutes “Japanness” in architecture remains as elusive as a Zen koan.

“Japan-ness moves roughly in 25- to 30-year cycles” (p. 103) notes Arata Isozaki in Japan-ness in Architecture, the latest manifesto in this intellectual lineage, which is at least as sophisticated, if not more provocative, than his peer Kisho Kurokawa’s Rediscovering Japanese Space (Weatherhill, 1989). For those who know Isozaki, this is a long overdue compilation of his twenty years of writing packaged under the eponymous title of Sutemi Horiguchi’s 1934 predecessor as a “tribute to Horiguchi’s taste, courage and scholarship” (p. 338) and awaited with as much anticipation as Charles Moore’s You Have to Pay for the Public Life anthology (MIT Press, 2001). For those unfamiliar with Isozaki’s writings, this is a refreshing discourse on the “problematics” of Japanese architecture - indeed on the dilemmas of all architecture in an increasingly globalizing milieuby a superior architectural mind, whose impeccable scholarship, breadth of both Eastern and Western history, and critical presence in Japanese Modernism enables him to take on well-worn subjects while revealing new insights at every turn.

Superbly translated by Sabu Kohso, the book’s quartet structure nonetheless seems relatively simple: Part I consists of seven chapters elaborating Japan’s embrace of Modernism and eventual globalization; Parts II, III, and IV discuss three historic paradigms as pointers to the dilemmas of Japan-ness. Perhaps one is better off not being bogged down by a linear reading, instead darting through it like a set of multicolored haikus - like Yoshida Kenko’s thirteenthcentury Essays in Idleness - each a whack of a Zen master’s stick. Whether a hypothesis validated by case studies or conclusions derived from meticulous research, the point is that there is more to digest in every individual fragment than the book as a whole.

Isozaki excavates the contradiction lurking behind the Ise shrine’s elusive history (Part II): its

“repetition of relocation and rebuilding repel[ling] the blind process of history” (p. 146) to preserve its “fabricated origin” (p. 169) and identity over time. An insightful trilogy on the Katsura Villa (Part IV) challenges Taut’s, Horiguchi’s, and Tange’s influential contemporary interpretations of the infamous retreat, positing a new one: Katsura as a subjective “Janus-like” construct appearing “as either shoin or sukiya, according to the viewpoint of the observer” (p. 281). Isozaki thus strips away the century-old veneer that has masked these two buildings as the predominant allegories of Japan-ness.

As such the book’s most refreshing contribution is the fourteen essays on the monk Chogen’s reconstruction of the Todai-ji temple (Part III). There are many things to digest here: Chogen’s reorganization of traditional canons, his political strategy to syncretise the worship of Ise and Todai-ji, and an extraordinary comparison of Chogen and Brunelleschi. But it is the unveiling of Todai-ji’s Southern Gate-house-the Nandai-mon-as the one extant Japanese historical masterwork, having “neither antecedent nor offspring” (p. 243), that introduces a new formal “constructivist” perspective of Japan-ness, debunking the austere, minimalist stereotype that has haunted the concept for decades.

Part I affirms Isozaki’s critical role in the dilemmas of contemporary Japanese architecture. Beginning at the cusp of Japan’s Modernization, from Wright’s Imperial Hotel to Tange’s Hiroshima Memorial, his exposure to the “clear advocacy of the modern subject” (p. 55) in the mid-fifties forges his rendezvous with the Metabolism movement in the sixties. And his suspicion of the Western plaza as Japan’s new democratic paradigm in the seventies fuels his “transplanted urbanism” (p. 75) in the controversial Tsukuba Center-literally inverting Michelangelo’s Campidoglio-in the eighties, all embodying his continuous struggle to marry Japanese and Western thought: "For Japanese Modernists - and I include myself-it is impossible not to begin with Western concepts. That is to say, we all begin with a modicum of alienation, but derive a curious satisfaction-as if things were finally set in order-when Western logic is dismantled and

returned to ancient Japanese phonemes. After this we stop questioning" (p. 65).

Perhaps these words best capture Isozaki’s conundrum: What is “Japanese” about Japanese architecture? The answer drifts somewhere between Japan and the West, somewhere between Japan’s own nostalgia and utopia, recurrently mutating and reincarnating itself, evading any fixed recognition. It is hard, even for Isozaki who has been at the very eye of the vortex, to objectify Japan-ness even as he cannot stop contemplating it. Like Walter Benjamin’s reading of Paul Klee’s “Angelus Novus” - the Angel of History-he gapes at a wrecking past, even as a storm irresistibly propels him into a future to which his back is turned. The debris is Japan’s traditions; the storm is Japan’s mutations.

Vinayak Bharne

Vinayak M Bharne

Vinayak M Bharne