Art, Indus Civilization

Sign up for access to the world's latest research

Abstract

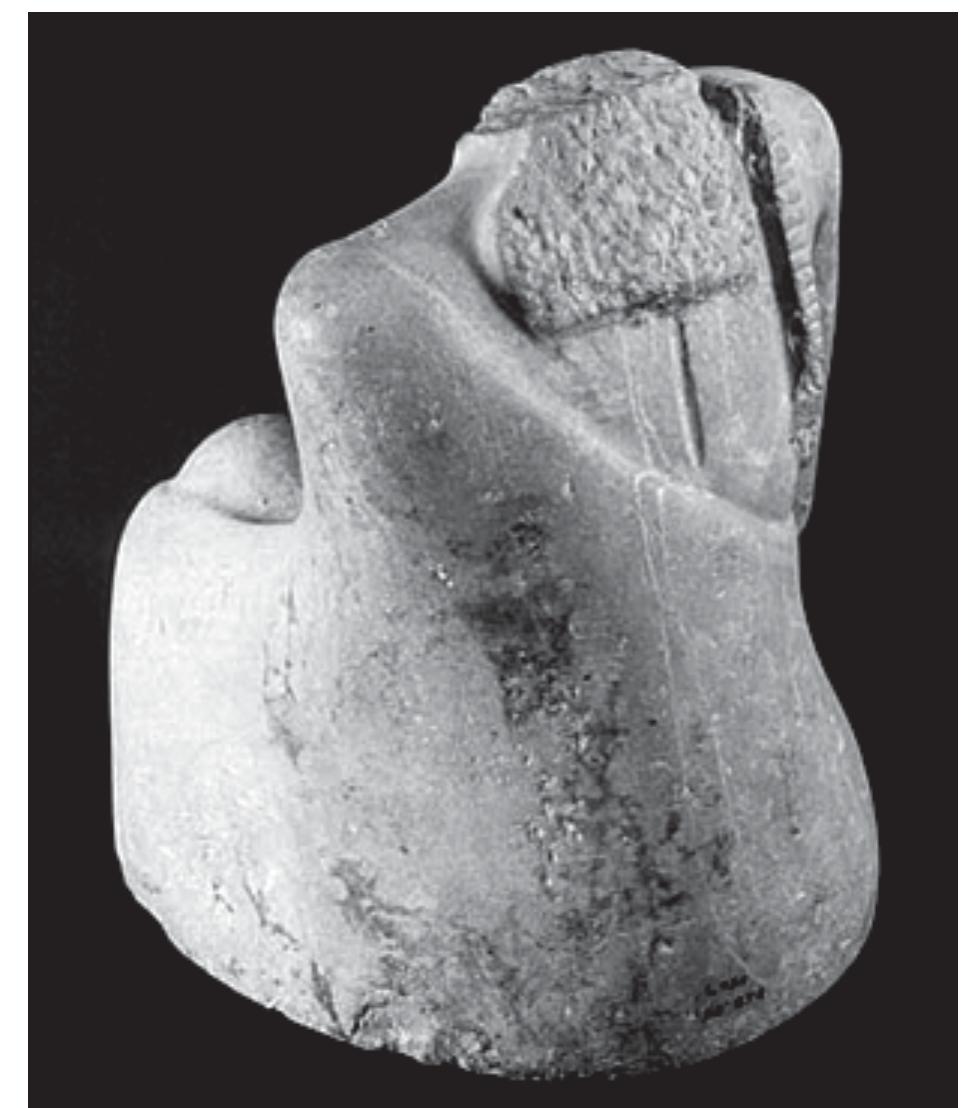

[The fact that the Harappan art reflects some of the essentials of the later day Indian artistic tradition is possibly the most important qualitative feature of this art. One finds it incredible that the ëintersecting circle motifí of some Harappan clay tiles found at Ahladino, Balakot and Kalibangan should occur on the top surface of the famous third century BC Bodhi throne of Bodh Gaya. The appearance of the famous ëpriest-kingí head and torso down to its gaze on the tip of his nose and even the way in which he is shown wearing a shawl are quintessentially Indian.]

Related papers

This paper presents the results of village to village survey conducted in entire Hanumangarh district during 2008 to 2012. During this survey, a total of 574 sites were visited and it revealed a number of new sites in the catchment area of major urban sites like Kalibangan, Sothi and Nohar. The results of the survey can provide vital contributions to our understanding of the rise and fall of Indus Civilization as a whole.

This article deals with architecture, temple design, and art in ancient India and also with continuity between Harappan and historical art and writing. It fills in the gap in the post-Harappan, pre-Buddhist art of India by calling attention to the structures of northwest India (c. 2000 BC) that are reminiscent of late-Vedic themes, and by showing that there is preponderant evidence in support of the identity of the Harappan and the Vedic periods. Vedic ideas of sacred geometry and their transformation into the classical Hindu temple form are described. It is shown that the analysis of the "Vedic house" by Coomaraswamy and Renou, which has guided generations of Indologists and art historians, is incorrect. This structure that was taken by them to be the typical Vedic house actually deals with the temporary shed that is established in the courtyard of the house in connection with householder's ritual. The temple form and its iconography are shown as natural expansion of Vedic ideology related to recursion, change and equivalence. The centrality of recursion in Indian art is discussed.

South Asian Archaeology 2001, Volume II, Historical Archaeology and Art History, 2005

This paper presents the results of village to village survey conducted in entire Hanumangarh district during 2008 to 2012. During this survey, a total of 574 sites were visited and it revealed a number of new sites in the catchment area of major urban sites like Kalibangan, Sothi and Nohar. The results of the survey can provide vital contributions to our understanding of the rise and fall of Indus Civilization as a whole.

Asian Perspectives, 2003

International Conference on Multidisciplinary Research, University of Jhang, (ICMR- 2022- SSH-69). , 2022

The stone art of ancient civilization or its being nurturing in the contemporary scenario, always speaks about its life patterns, and plays a vital role in developing of cultural and societal norms with rituals, and professions of the time. Indus Valley Civilization is one of the most primogenitor and substantial civilization of Indian Subcontinent as an urban settlement, known for remarkably sculpture, stamp and seal carving and decorative crafts; stands parallel to the renowned civilization of Ancient Egypt and Mesopotamia. It became a source of cultural extension as an inspiration for the contemporary artists of stone art. This paper focuses on the study of the indigenous art of stone carving and the contribution of the people of Indus Valley that suggests the better understanding of their life pattern, culture, religion, sociology, profession, expertise, and technology. The art and cultural extension of the Indus valley Civilization has nurtured through some of these crafts and their technologies are still in practice in India and Pakistan. Through the analysis of stone art of Indus Valley Civilization, it may also be possible to survey the connections and modification of this particular art in the contemporary stone artwork of Pakistani artists.

Preface It is appropriate to add a comment on the so-called undeciphered seals of the civilization cited by Vasant Shinde in this exquisite overview of the issues and prospects related to the studies of Harappan (what I call Sarasvati) Civilization. The decipherment or rūpaka 'metaphor' or rebus translation of the inscriptions on two seals cited from Rakhigarhi is presented in this monograph. The River Sarasvati is the epicentre of the civilization with sites like Kunal, Bhirrana,Mitathal, Rakhigarhi on this river basin, taking the roots of the civilization back to ca. 7th millennium BCE. Over 80% of the sites discovered so far are on the River Sarasvati basin. Seal 1 and 2 have identical Pictorial motifs: one-horned bull PLUS standard device in front. These pictorial motifs are read as rūpaka, 'metaphors' or rebus renderings in Meluhha. I suggest that these two seals,like other 8000+ Indus Script inscriptions are wealth accounting ledgers, metalwork catalogues. Hieroglyphs on pictorial motifs of two Rakhigarhi seals, Seals 1 and 2: 1. Young bull खोंड khōṇḍa 'A young bull, a bullcalf'; rebus kundaṇa, 'fine gold' (Kannada); Rebus: kō̃da कोँद 'furnace for smelting': payĕn-kō̃da पयन्-कोँद । परिपाककन्दुः f. a kiln (a potter's, a lime-kiln, and brick-kiln, or the like); a furnace (for smelting). -thöji - or -thöjü -; । परिपाक-(द्रावण-)मूषाf. a crucible, a melting-pot. -ʦañĕ -। परिपाकोपयोगिशान्ताङ्गारसमूहः f.pl. a special kind of charcoal (made from deodar and similar wood) used in smelting furnaces. -wôlu -वोलु&below; । धात्वादिद्रावण-इष्टिकादिपरिपाकशिल्पी m. a metal-smelter; a brick-baker. -wān -वान् । द्रावणचुल्ली m. a smelting furnace. 2. Standard device of two joined parts सांगड sāṅgaḍa 'joined parts' (the parts joined are: lathe PLUS portable furnace): sangaḍa 'lathe' PLUS kammata 'portable furnace' rebus: sangarh 'fortification' PLUS kammata 'mint, coiner, coinage'. (Variant rebus readings reinforcing the nature of the trade transaction recorded on the inscription: jangad ''goods invoiced on approval basis'; jangadiyo 'military guard accompanying treasure into the treasury';samgraha, 'catalogue' of shipment products.) Hypertext on text of inscription: Seal 1: Sign 397 dhāī ''a strand (Sindhi) Rebus: dhatu 'mineral ore' dhāī f. ʻ wisp of fibres added from time to time to a rope that is being twisted ʼ, L. dhāī˜; B. Throw of dice: dāˊtu n. ʻ share ʼ RV. [Cf. śatádātu -- , sahásradātu -- ʻ hun- dredfold, thousandfold ʼ: Pers. dāv ʻ stroke, move in a game ʼ prob. ← IA. -- √dō] K. dāv m. ʻ turn, opportunity, throw in dice ʼ; S. ḍ̠ã̄u m. ʻ mode ʼ; L. dā m. ʻ direction ʼ, (Ju.) ḍ̠ā, ḍ̠ã̄ m. ʻ way, manner ʼ; P. dāu m. ʻ ambush ʼ; Ku. dã̄w ʻ turn, opportunity, bet, throw in dice ʼ, N. dāu; B. dāu, dã̄u ʻ turn, opportunity ʼ; Or. dāu, dāũ ʻ opportunity, revenge ʼ; Mth. dāu ʻ trick (in wrestling, &c.) ʼ; OAw. dāu m. ʻ opportunity, throw in dice ʼ; H. dāū, dã̄w m. ʻ turn ʼ; G.dāv m. ʻ turn, throw ʼ, ḍāv m. ʻ throw ʼ; M. dāvā m. ʻ revenge ʼ. -- NIA. forms with nasalization (or all NIA. forms) poss. < dāmán -- 2 m. ʻ gift ʼ RV., cf. dāya -- m. ʻ gift ʼ MBh., akṣa -- dāya-- m. ʻ playing of dice ʼ Naiṣ.(CDIAL 6258) தாயம் tāyam, n. < dāya. A fall of the dice; கவறுருட்ட விழும் விருத்தம். முற்பட இடுகின்ற தாயம் (கலித். 136, உரை). 5. Cubical pieces in dice-play; கவறு. (யாழ். அக.) 6. Number one in the game of dice; கவறுருட்ட விழும் ஒன்று என்னும் எண். Colloq. rebus: dhāˊtu n. substance ʼ RV., m. ʻ element ʼ MBh., ʻ metal, mineral, ore (esp. of a red colour) ʼ Mn., ʻ ashes of the dead ʼ lex., Pa. dhātu -- m. ʻ element, ashes of the dead, relic ʼ; KharI. dhatu ʻ relic ʼ; Pk. dhāu -- m. ʻ metal, red chalk ʼ; N. dhāu ʻ ore (esp. of copper) ʼ; Or. ḍhāu ʻ red chalk, red ochre ʼ (whence ḍhāuā ʻ reddish ʼ; M. dhāū, dhāv m.f. ʻ a partic. soft red stone ʼ (CDIAL 6773) Semantic determinative. Sign 162: kolmo 'rice plant' rebus: kolimi 'smithy, forge' Sign 162 Sign 397 and possible cognates of 'strand': Seal, Rakhigarhi (Note: For readings of other Rakhigarhi seals see: http://tinyurl.com/zat4ty2 Two images of a seal remnant at Rakhigarhi. From l. to r. kolom 'three' rebus: kolimi 'smithy, forge'; kuṭilika 'bent, curved' PLUS dula 'pair' rebus: kuṭila, katthīl = bronze (8 parts copper and 2 parts tin) PLUS dul 'metal casting'; (split parenthesis as a circumscript is a break-out of a bun-ingot or lozenge or oval shaped ingot) muh 'ingot' PLUS baṭa 'quail' rebus: bhaṭa 'furnace' PLUS sal 'splinter' rebus: sal 'workshop' bicha 'scorpion' rebus: bicha 'haematite, ferrite ore'; tutta 'goad' rebus: tuttha 'zinc sulphate'; dāṭu 'cross' rebus: dhatu 'mineral' karṇaka 'rim of jar' rebus: karṇī 'supercargo' karṇika 'helmsman, scribe,engraver'. Harappan Civilization: Current Perspective and its Contribution – By Dr. Vasant Shinde by admin | Feb 1, 2016 By Dr. Vasant Shinde Introduction The identification of the Harappan Civilization in the twenties of the twentieth century was considered to be the most significant archaeological discovery in the Indian Subcontinent, not because it was one the earliest civilizations of the world, but because it stretched back the antiquity of the settled life in Indian Subcontinent by two thousand years at one stroke. Vincent Smith (1904), one of the leading historians of the era, had written, in the beginning of the twentieth century, that there was a wide gap (Vedic Night) or a missing link between Stone Age and Early Historic periods in the Indian History and the settled life in this part of the world began only after 6-5 century BCE, probably during the Stupa (Buddhist) period. The discovery of the Harappan Civilization proved him wrong and the Indian Subcontinent brought to light the presence of the first civilization that was contemporary to the Mesopotamian and Egyptian Civilizations. This Civilization was unique compared to the two contemporary civilizations on account of its extent and town planning. Extent-wise it was much bigger in size than the Mesopotamian and the Egyptian Civilizations put together and spread beyond the Subcontinent. Its town planning consisting of citadel and lower town, both fortified and having a checkerboard type planned settlement inside them, was a unique and unparallel in the contemporary world. Intensive and extensive works have brought to light over two thousand sites till date. The distribution pattern suggests that they were not only spread over major parts of western and north-western Indian subcontinent, but its influence is seen beyond, up to the Russian border in the north and the Gulf region in the west. In true sense this was the only civilization in the contemporary world, which was an international in nature. The Indian subcontinent has all the favourable ecological conditions to give birth to the early farming community. The Southwest Asian agro pastoral system with wheat, barley, cattle, sheep and goats had spread through Iran and Afghanistan to Preceramic Mehrgarh in Baluchistan by about 7000 BC. Early Mehrgarh lithics, loaf-shaped mud bricks, female figurines and burial practices all suggest Southwest Asian influence from somewhere in the Levant or Zagros regions. The origins of village life in South Asia were first documented at Kile Ghul Mohammad in the Quetta valley (Fairservis 1956), then at the site of Mehergarh at the foothill of the Bolan pass on the Kacchi Plain on the Indus Valley (Jarrige 1984). Both these sites and numerous other in this region demonstrate cultural development from the seventh millennium BCE to the emergence of the of the Mature Harappan phase in the middle of the third millennium BCE. As far as the climatic conditions during the Early-Harappan and Harappan times are concerned there are two conflicting interpretation. The data for paleoclimate reconstruction were obtained from Rajasthan lakes such as Didwana, Lunkarsar, Sambhar and Pushkar. The studies carried out by Singh et al (1990) have suggested that the mid-Holocene climatic optimum coincides with the mature phase of the Harappan Civilization and its end with a sharp excursion into aridity. Most interesting example cited is the occurrence of Cerealia type pollen and finely comminuted pieces of charcoal found in these lakes at 7000 BP, which has been interpreted as evidence for forest clearance and the beginning of agriculture. On the other hand, the studies carried out by Enzel et al. (1999) show that there is no simple correlation between favourable climate and the archaeological data. They have suggested that the most humid phase at Lunkaransar has been dated to between 6.3-4.8 kys with abrupt drying of the late sometime around 4.8 kys. During the period between 6.3-4.8 kys the lake was freshwater and never dried up. Significant shift in the carbon isotope values are also seen in this period. The most flourishing Harappan phase (Mature) is thus does not correlate to the favourable climate but indicates that it rather developed in a period of deteriorating climatic conditions. They have concluded that the Harappan Civilization was not caused by the presence of favourable environment. More data in this respect needs to be generated in nature future.

Loading Preview

Sorry, preview is currently unavailable. You can download the paper by clicking the button above.

References (13)

- Allchin, F.R. 1992. An Indus Ram: A Hitherto Unrecorded Stone Sculpture from the Indus Civilisation. South Asian Studies 8: 53-54.

- Ardeleanu-Jansen, A. 1984. Stone sculptures from Mohenjo-Daro. In Jansen, M. and Urban, G. (eds.), Reports on Field Work Carried Out at Mohenjo- Daro, Pakistan 1982-83 by the ISMEO-Aachen University Mission, Interim Report. Aachen: ISMEO-RWTH, Vol. I, pp. 139-157.

- Chanda, R.P. 1929. Survival of the Prehistoric Civilisation of the Indus Valley. Calcutta: Archaeological Survey of India.

- Chengappa, R. 1998. The Indus Riddle. India Today 23(4): 44-51 (for Dholavira specimens).

- Jarrige, Catherine. 1984. Terracotta human Figurines from Nindowari. In B. Allchin (ed.) South Asian Archaeology 1981. Cambridge, pp. 129-134.

- Manchanda, O. 1972. A Study of the Harappan Pottery. Delhi: Oriental Publisher.

- Marshall, J. (ed.). 1931. Mohenjo-Daro and the Indus Civilisation. 3 vols. London: Arthur Probsthain.

- Ratnagar, S. 2004. Trading Encounters: from the Euphrates to the Indus in the Bronze Age. Delhi: Oxford University Press.

- Satyawadi, S. 1994. Proto-Historic Pottery of Indus Valley Civilisation: Study of Painted Motifs. Delhi: D.K. Printworld.

- Starr, R. Indus Valley Painted Pottery. Princeton: University Press.

- Weiner, S. 1984. Hypotheses Regarding the Development and Chronology of the Art of the Indus Valley Civilisation. In B.B. Lal and S.P. Gupta (eds.), Frontiers of the Indus Civilisation. Delhi: Books and Books, pp. 395-415.

- Winckelmann, S. 1994. Intercultural relations between Iraq, central Asia and northwestern India in the light of squatting stone sculptures from Mohenjo-Daro.

- In A. Parpola and Koskikallio (eds.), South Asian Archaeology 1993. Helsinki: Sumomalainen Tiedekamia, pp. 815-831.

DilipK Chakrabarti

DilipK Chakrabarti